Lighting the Set

by Adam "Ready" Richman

Adam “Ready” Richman, cinematographer, dives deep into what it was like to light the set with Smokin’ Electrics and industry pros Zac Baney and Eric Corriea.

It is accurately credited that this music video was inspired by the Great Again L.P. album artwork. The story and characters were derived from characters drawn and traced by Pp, showcasing historical tropes and struggles under the shadow and constraints of a great capitalist pyramid. It’s from these visual themes, and those developed within the consensus-built treatment, that my relationship to the cinematography of Strangetown began.

COLOR & TONE

When we realized that the music video was to be a tour of the pyramid, with Pancho ascending his way to the top, some specific decisions on tone and color became immediately clear. In the album art, characters (and the worlds they represent) are assigned specific colors by class. In the music video, these same rules are strictly followed. The “red” folks (dressed in red) represent the working class, the “gold” folks (dressed in gold) represent the elites, and the “purple” folks (dressed in purple) represent power, structure, and control. It was important to me, when collaborating with each of the different vignette leads, that we stayed true to at least this one creative constraint: color. By defining such a strict and purposeful limitation from the start, collaborating artists were invited to go to any extreme, so long as this one rule was respected. Trusting our collaborators became our biggest asset. The results were spectacular.

As a cinematographer, the best way for me to create incredible material is to have incredible material to photograph in the first place. “Put your money in front of the lens,” goes the old adage. With Strangetown, we did exactly that. No fancy camera tricks or expensive post-production effects, just incredible art and committed performers in front of the lens.

LIGHTS TO MATCH

The lighting package was, of course, built to match. We needed the concept of color, tone, pace, and contrast to be mirrored in each of the lighting decisions. We knew that our tiny out-of-pocket budget would not be able to afford us the modern conveniences of full color RGB LEDs, HMI’s, or even Kino arrays, so we went old school: tungsten and gels. With few exceptions, almost the entire package was tungsten. Two speciality units, an Arri SkyPanel s60 and a 4’ Kino Select RGB LED, were begged and borrowed from two of my oldest and dearest friends, Zac Baney and Eric Corriea, who joined the shoot from Los Angeles for the weekend. Together, they were responsible for lighting Strangetown. In total, we hung over 100 lights, and we’ll get into the specifics below.

We sourced all of our units from DTC Grip & Electric in Oakland, who were incredibly supportive from the start. If you need G&E in the Bay Area, DTC is your spot. One tricky part of the equation was getting the gear to the warehouse. We weren’t renting a truck from DTC, partially because we couldn’t afford it, and partially because it didn’t make sense (it would have required a permit to park it, and we would have just emptied all its contents into the warehouse anyway). This meant that every piece of gear had to be loaded into a personal vehicle (or, in our case, three vehicles). Fortunately, our community had our back, and we were able to borrow both a proper (albeit small) box truck and a full size pickup from our build team (thanks Wolfgang and Way) to ease the transfer. Since the gear wasn’t ever leaving our warehouse location, and we weren’t parking a truck outside, we didn’t need a permit, and we didn’t draw unnecessary attention to ourselves by advertising the film shoot inside.

UTILIZING THE SPACE

They say, “write what you know, write what you have.” Each vignette was ultimately written with the unique spaces of 30 West, the warehouse we used as our set, in mind.

Having access to a mostly empty ~8,000 sq. ft. warehouse for the better part of a month was an invaluable resource and, as I’ve often argued, one of the primary reasons the shoot was able to prosper. We simply could not have produced this project without the unrelenting support of two Oakland heroes: Paul “Savage Paul” Savage and Tanya Retherford. They were the powerhouse duo that helped negotiate our mostly “open door” policy with the collective tenants, allowing access to the space for over a month. They had recently acquired and taken responsibility for the space and were in the process of preparing it to become the thriving artist community it is today, and they helped us schedule our shoot before any major construction within the space began.

We did what we could to pay them back for the access: under the motto of, “leave it better, leave it beautiful,” we rallied the team and scrubbed walls, knocked out ceilings, swept floors, and blessed the bathrooms with soap and water (for what seemed like the first time in years).

CHALLENGES IN THE WAREHOUSE

Shooting in a mostly empty ~8,000 sq.ft. warehouse without anything resembling a proper “grid” is not without its challenges.

For one, it was immediately apparent that a scissor lift would be necessary expense. While it proved to be an invaluable tool, what once seemed like an infinite desert of vast open space quickly shrank as sets and tools and people started moving in. Navigating around an active construction site during our week of prep to hang lights became a constant negotiation.

Next, if we were to have any shot at making our production days, the skylights that let in beautiful diffused natural sunlight all day had to go. This required sending the scissor lift outside to get roof access, and dropping 200’ of black visqueen atop them to black-out the set (consequently using most of the sandbags we rented). Once we had the set blacked out, we were able to really start to see what we were working with.

PLAN YOUR SHOOT. SHOOT YOUR PLAN.

The practical strategy for lighting the space was essentially to have little to no units on the ground, favoring “environmental” lighting. There would be too many people in too tight of spaces, excess shadows would be an issue, having stands in the way needed to be avoided, and just the general considerations of safety all forced us into the obvious choice. The warehouse did not have a proper “grid” system for hanging lights, and so getting things rigged became a never-ending dance of available grip gear. We started with mafers and blocks of wood, moved to cardellinis, and ultimately found c-clamps to be the most reliable at rigging to the existing “T” beams in the sky. Fun fact: we used every safety chain DTC had left in inventory.

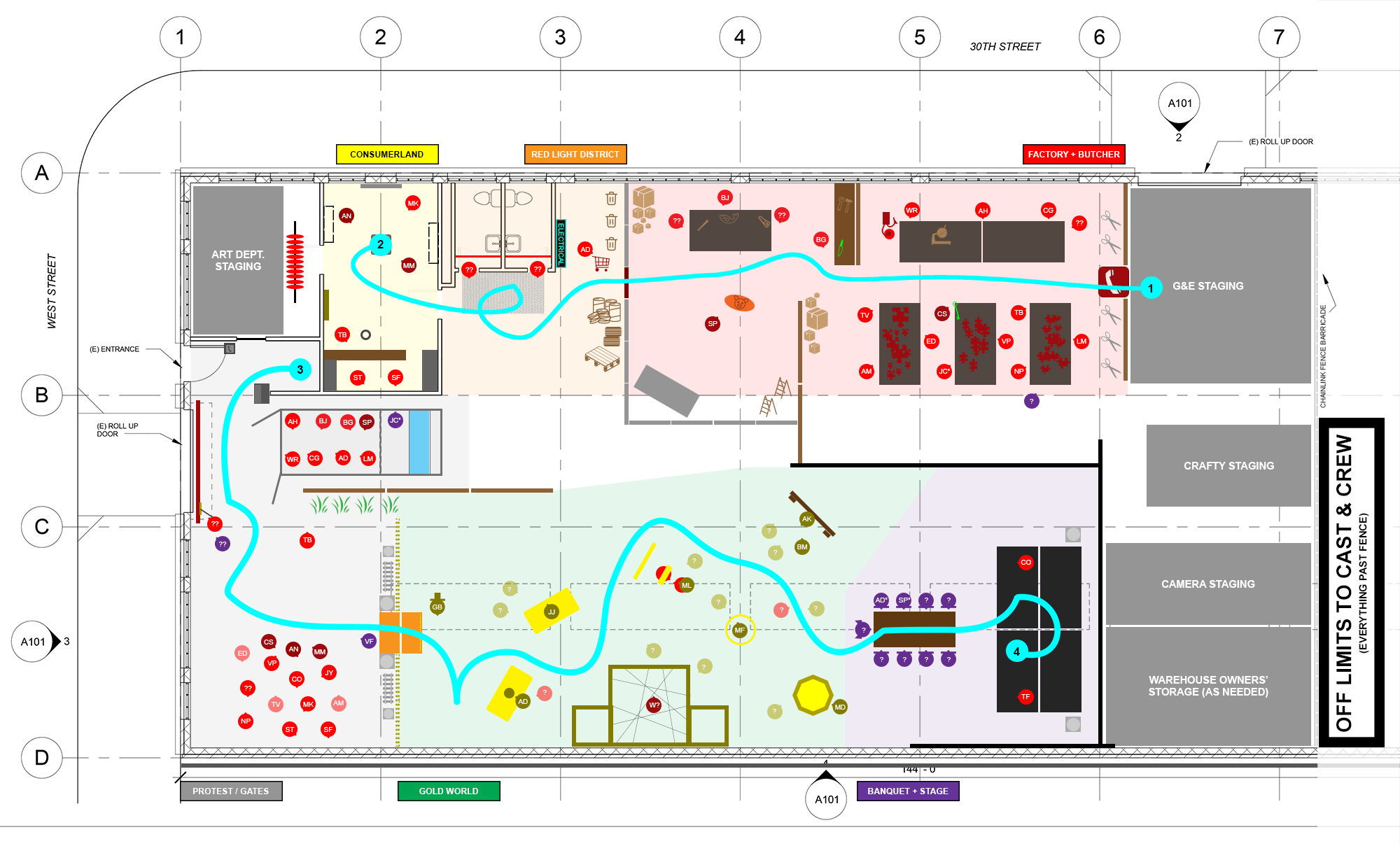

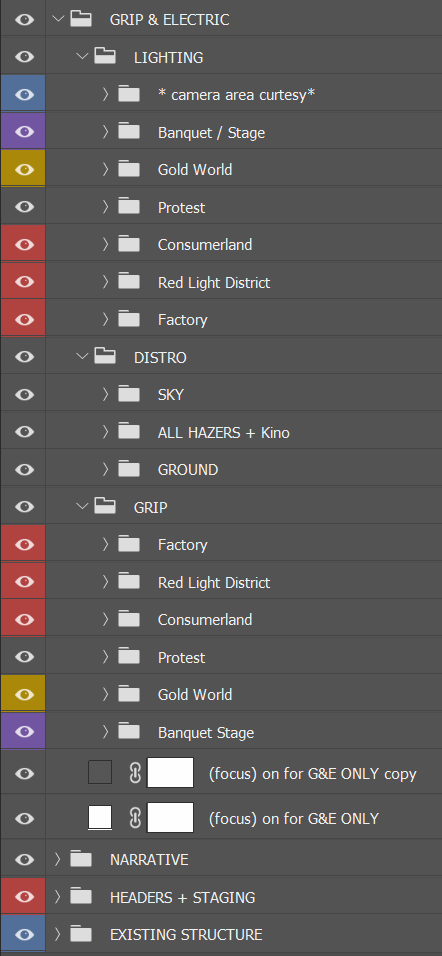

Before we even picked up the gear, however, I spent the better part of a week in Photoshop creating an overhead diagram for the benefit of the entire crew. This diagram proved essential to communicate key information among the 100+ collaborators.

For our Smokin’ Electrics, Zac and Eric (affectionately refered to as “The Boys” going forward), I added layers with additional info for them to use as a guide when they arrived to set. Each space had clearly defined the units, the direction, and the power runs based on the pseudo-grid we were building off of in the sky. After going through the plan in detail with The Boys, they made some important changes (including completely redrawing the power runs to be much simpler than I had defined) and we marched forward. I made print-outs on 11×17’, laminated them, and distributed copies throughout the set for them to reference. This mostly freed me up to attend to an ever-growing list of tasks as the shoot days approached.

Now, at the very first meeting, as I was explaining what we were hoping to accomplish, The Boys recommended we run every light through separate DMX channels and control things wirelessly from their iPad using Luminair. It was an ambitious and novel idea that I hadn’t considered, and one that proved to be an amazing asset not just for the speed of production, but in opening up creative possibilities for each of the many vignettes. Watching the two of them run around the set tagging lights and then fading them up or down on command turned the set into a very literal cinematographer’s playground.

The general flow was to get all the lights rigged up, power them in groupings, tag them with a unique channel, then focus them on their intended targets while blocking. Many of the lights were setup to illuminate the environment, but a handful of “key” lights were placed throughout each scene and faded up or down as Pancho engaged with different elements or people in the vignette.

CAMERA

Before we get into the specifics for each scene, a note on camera and movement. The original concept for this video was that it’d be shot entirely on gimbal, using a GH5 that I owned. We used Sigma ART series glass, the 18-35mm at f/1.2 (via a Metabones Speedbooster) for everything. In retrospect, a larger sensor would have been a better choice, as we ended up needing significant noise reduction in post production. Admittedly, I was lured in by the promise of small and lightweight 10-bit 4K, instead of trusting my old favorites in the Sony a7 series who, despite their lower bit depth, tend to produce much more pleasing images in lower light scenarios and perhaps would have been a better camera for the job.

We intended to shoot everything for the project using a gimbal, the Tilta Gravity G1, which I can confidently say that nobody should buy ever. That said, I’m selling one if anyone’s interested. Name your price. The gimbal was worthless to us; it shit the bed during our prep and, despite some helpful attempts by the folks at Tilta over the phone, it became clear it needed to get sent back home to China. Apparently it could not handle the weight of the small but robust GH5 and the motors from the Nucleus-M wireless follow focus (well under the advertised weight limit, for the record).

Not to be crippled by the technological defeat, we decided in that moment that I would operate the entire shoot handheld. It was something I was comfortable with, having operated handheld on dozens of projects and despite the modern flare a gimbal would have added, handheld became the obvious clear choice as soon as our first rehearsal was up: the film wanted the momentum, and I wanted the flexibility. So with Rikuto Sekiguchi on the sharps, we were ready to roll.

PAINTING WITH LIGHT

John Alton, a Hollywood cinematogralpher best known for his film noir work in the 40’s and 50’s, popularized the phrase, “painting with light,” with his debut book of the same title. To me, this idea has always rung true and has thus become a credo to follow as a cinematographer. Strangetown’s unique vignettes were the perfect canvas to excercise precise lighting control to help paint a complex and important story. Let’s dive into each scene in detail.

THE OPENING

For the opening scene, we set up handheld, with me sitting on a doorway dolly on track that begins close in on the bird cage, and works back at a diagonal to center stage at about 20 feet away. As the dolly moves finishes, Roxy, one of our talented actors, walks by to wipe the frame (later revealing the Factory). The stage was constructed by four 4×8’ stage flats that were generously donated by Eddy over at Event Magic (along with dozens of props and set pieces from all 7 vignettes).

On the lighting side, we mostly relied on two focused and softened Leiko Source 4s at 26-degrees, hung overhead camera and frontal. One illuminated Pancho with a nice tight circle, and another on the bird cage (a symbol borrowed from the “canary in a coal mine” legends whereby the cage is used to represent upcoming danger; it’s purple phone line a subtle nod that the call from the Red World folks is being tapped by those in control, represented by purple as discussed above). The birdcage’s unit is faded up as the scene begins (it’s also trimmed down with an iris). Behind Pancho, we relied on the soft backlight of a 2K zip hung up and behind him that faded up with the scene as well.

The seemingly simple “Strangetown USA” sign was a huge undertaking that was constructed over the course of our entire build week. Garett, our master sign and graffiti artist, designed the welcome sign, I jigsaw’d it out by hand, and Dillon, Trevor, Nick, and Justin wired it up with a combination of “cafe bulbs,” LEDs, and strips of gel for coloring. The bulbs were set to their own DMX channel so they could be faded up and down as it was lowered. Once created, the now quite-heavy sign needed to be rigged to the ceiling. Enter The Boys and Savage Paul, who developed a pulley system that allowed it to be lowered safely on cue by a team of two who were hidden behind the 20×40’ black solid at the back of the stage.

Like each vignette, timing was everything. Here, the challenge was landing the dolly move in combination with the sign lowering, in combination with the song and intro lighting cues, plus the final wipe from Roxy.

THE FACTORY

With set design by Chris Swimmer, support from Trevor Banta and with Ad Naka on the 1-2-3-4’s for the choreography, this scene was easily our second-most involved. Pancho enters a factory full of workers (all in red jumpsuits) and pushes a cart past rows of e-waste before eventually entering a butcher shop. As we track laterally on ~30’ of dolly track, an important key is stolen off of a guard (wearing purple) who is seen briefly in the foreground; the key is passed off to Pancho, foreshadowing a later scene.

On camera, the move was simple (G). I was seated on an apple box taped to the doorway dolly (for stability) while my dolly operator kept an eye on their dedicated wireless video feed that was helping them keep pace with Pancho (the rig was mounted to the handlebars). A the end of the track, after we pass by the rows of workers, I step off the dolly and continue the move on foot through the factory towards the butcher shop, passing a worker who send sparks from an angle grinder in front of lens (practical effect). We used a 4×5.65” clear filter and wrapped the camera in my hoody to keep it safe.

Lighting this scene began with hanging the practical factory bulbs strategically over the tables in a symmetrical way (E). Major kudos to director Dillon Morris who, through a complicated web of parachord, managed to get these perfectly symmetrical. We wired these to their own channel, and were able to cue them brighter as the key is passed off to Pancho, accenting the moment. Lighting continued with five 300w fresnels, gelled red, and aimed at each visible corner of the factory (B). Two 2k zip lights were placed at the back corner of the set and used to splash the rear row of workers from behind, giving them a slight edge (C). A 1k open-face was placed behind the red telephone booth to give Pancho a backlight as he exited at the top of the scene. The Skypanel was set to purple and floppies were used to focus a soft beam onto the guard in the foreground to further enforce the purple theme (F, off-screen, casting the purple light in the foreground). My personal flashlight and it’s tiny, focused beam, was set up on a c-stand and aimed at the key in the pocket of the guard, allowing it to be a stop or so hotter than the rest of the scene to help draw attention to it (D). Some opal was taped to the front to diffuse it slightly.

Pancho’s path was designed to be straight down the aisle between all of the tables, and thus he was able to be illuminated by two crossing Source 4’s – one behind him that had a half-double bottom scrim (so it wasn’t as hot when he was closer to it, as the source was mounted directly above the telephone booth he walks out of at the beginning) and one in front of him placed ahead of his path in the Butcher shop (A). Each were doored-in to create a thin rectangle and provide Pancho with the only “white” light in the scene, allowing him to “pop” using color as a separation device. Both were nice and tight 19-degree lenses.

During the rehearsals, each of the units were balanced, keeping the flashlight and the sparks from the angle grinder in consideration. Cues were setup for when Pancho left the room (everything accept the red on the walls would fade out, bringing attention to the Butcher shop in the foreground). Ad Naka shouted a count while we rolled so our performers could keep pace and stay in sync, this proved super important for helping sell the “factory vibe.”

THE BUTCHER

Pancho continues seamlessly into the Butcher shop from the Factory, and the shot continues unadulterated. Butchers are seen smashing and cutting until we come upon Savage Paul, who takes an active chainsaw to a real deceased pig. The scene is intentionally cringe-worthy, and the flying pig bits that catch the backlight are certainly not faked.

Given the nature of what was occurring here, strong backlights were employed. A snooted yellow tungsten construction light (like the kind from Home Depot) was used as a motivating backlight / key for the scene. It was setup in the corner and aimed towards the lens. In the two other far corners of the room, two 2K zip lights were used at very low levels to give the slightest edge to the butchers at each of the table surfaces. A rotating red “lighthouse light” was anchored to the wall, signalling danger and used practically. Watch the scene again and see if you can catch the flaming Rueben’s Tube we pass by briefly; Savage Paul constructed this in what amounted to his “off-time” whenever he was not tending to any of the other active “fires” on deck. Pun intended.

Perhaps the most exotic of lighting decisions came, however, from something that I discovered on the fly by surprise. The “slits” of light that appear and flare the lens directly behind our pig butcher were created by giving an inch or so’s worth of separation between the set walls (A, B, C above) with three source 4’s rigged at camera lens height and behind the walls by about 10’ (roughly from where the above photo was taken). From behind, it looked as if we were needlessly illuminating the back of the set walls. From inside the set, with the help of a hidden fog machine we’d engage sparingly, the result was three clean, direct, and somewhat unnatural “slits” of light that help to make the scene incredibly jarring. This one wasn’t on the diagram, but happened as I walked past and got stung by light through a mistaken existing crack in the seams —I immediately loved it.

THE RED LIGHT DISTRICT

Pancho continues out from the factory and into the streets of the Red Light District. Walking past (and himself not noticing) a houseless person digging through a shopping cart amidst a graffiti’d wall littered with hidden messages. He is approached by two women before eventually entering McBigley’s (often referred to internally as Consumerland).

The first unit we feel is a strong “street light” backlight via a Source 4 on Pancho and our houseless person. This was meant to showcase the graffiti mural, but also to give an edge to Adam Dainowski, who played our houseless extra. We’ve had reports of folks needing to watch a second or third time to catch that there is even a person there, which speaks volumes to the intent of the scene. As Pancho exits the Factory (on a red carpet, no less) and enters a new, more subdued world, the primary source of lighting is a massive octopus of light formed by a dozen “china balls” wired together. Each ball was either red, pink, or white, and each of the globes were sent to different DMX channels and set to fade up and down randomly. The idea was to give the space an uneasy feeling. The women from the “windows” were actually staged in each of our two set bathrooms. Black duvetyne was used to hide the toilets and sinks, and two gel’d red 2’ x 4-bank “Fat Boy” Kinos were rigged overhead by screwing baby pins directly above the door frames inside the bathroom, hidden from camera. They dropped the perfect pool of eerie red light.

MCBIGLEY’S CONSUMERLAND

Pancho continues uninterrupted through McBigley’s, where he’s offered a shot of ketchup as a patron consumes a burger made of cell phones, freshly microwaved by the kitchen staff behind the counter. In the background, a purple police officer eats in the drive-through window, sitting in the van that will later be unlocked to reveal a flood of now-freed protestors.

This scene was deceptively simple. We hung two 300-watt units in the top corners of the room and aimed those at each of the walls full of shelves that we, unfortunately, quickly pass by. The shelving units were full of some amazing lost details; I’m hoping Ad has forgiven me. Our 4×4’ Kino Select was placed up and behind the counter to serve as a backlight for Pancho and an RGB-controllable and dimmable top-light for the servers. Primary illumination came from a 2K space-light that was skirted, gel’d, and hung directly over the center of the room. When the camera lands on Pancho in the chair, there is a 2K zip mounted directly above camera that provides the bulk of the frontal illumination at the tail of the scene. Finally, in the deep background, a Source 4 was placed on a stand and aimed into the police van parked at the drive-through window. All of these units dim and change colors throughout the scene as things amplify and focus is intended to shift.

This scene and the Red Light District were essentially designed around the existing spaces at 30 West. The biggest challenges came during prep — constructing the McBigley’s sign that’s used not just as a beautiful illuminated statement piece, but also to hide an existing heater comes to mind. LED’s and a variety of diffusion was used to make this pop with Dillon again on the soldering iron and Ad directing the director. Further, the drop ceiling that existed when we arrived needed to be tore out so we could place lights higher in the room and out of frame — a chore Pancho himself had a heavy hand in.

THE PROTEST

Red and gold and purple collide in our most hectic of scenes. Protestors storm the “Golden Gates” as police hold a barrier. Only Pancho, carrying the golden key (stolen off a guard at the factory), is granted entry to the exclusive party for the elites.

For this scene, our scissor lift was the MVP. All of the units were hung to the sky to keep clear paths for everyone who was moving on cue — the protestors, Pancho, and camera team. To start, my flashlight was again employed on the “STPD” sign seen briefly as the scene wipes into view. The same Source 4 that was used to illuminate the van’s cop driver was refocused to shine through the van’s empty back window, and give Pancho and nice strong key as he releases the protestors from the van. Another Source 4 is aimed and shaped on the graffiti mural in the background, giving it some beautiful fall-off that highlights the clown’d Uncle Sam as he feeds a variety of vices to the masses. Watch again and investigate the details on this mural.

A standing police officer is watching over and insuring a red-suited worker is doing their community service (painting over the mural), but they are soon punched square in the jaw and sent flying by our hero Pancho. A strong backlight from a Source 4 helps separate this action from the rest of the commotion, and soft bags were placed among the trash piles to insure a soft landing.

We had talked about hanging two 2K nook lights in each corner of the protest scene up and behind all of the action. The thought was we would put blue gel on one and red gel on the other, alternating between the two with Luminair. The Boys made a compelling argument to simply raise the SkyPanel to top floor of high-roller and use it’s built-in “police car” chase mode instead of trying to make the effect manually. They were absolutely correct; this was a much more effective approach. The SkyPanel serves as our primary key in this scene, and adds a ton of flavor to the scene, making it feel real.

As Pancho approaches the golden gates, he and the guard are illuminated by a strong Source 4 backlight that’s snooted away from the rest of the action and picketeers. Four 300w tungsten fresnels were aimed at the golden gates, specifically on the front of the gold lame that was in use as set decor. This gave the fabric a much needed sparkle, but also helped to hide the rest of the set that was just behind the pseudo-walls.

This was the first scene we shot of the video, and the whole warehouse really came to life once everyone on crew got to see things on camera for the first time — suddenly all those hours of hard work and dedication made some semblance of sense.

THE GOLD WORLD

This was easily our most complex scene, and thus we devoted an entire production day to it. It used more units than any other scene, had more characters and more choreography, and required everything to come together in perfect unison for a full 1:30m+ before we could call it a wrap on the production. In this scene, Pancho takes on the world of the elites, The Gold World, making his way to the banquet table, and the stage that seemed destined for him. But amidst the party there are Red World revolutionaries (can you spot all of them?), and Pancho as their undercover leader comes with a surprise of his own. In the end, is he one of us, or one of them?

The Gold World saw our most rigorous lighting configuration yet. For starters, to get the “gold” in the world to really pop, we hung 8×8’ gold lame on the slanted roof at a downward ~30-degree angle in the center of the world, filling it in with a Source 4 and 50-degree lens. On the walls of the gold world, two Source 4’s with gobo patterns added a fancy flair to the world. They were kicked slightly out of focus so as to not be too distracting, but still make the walls more interesting than the otherwise bland brick. Between this and a 2K spacelight, again somewhat center-world, we developed our base illumination.

Each of the vignettes then had their own specials added. Avi’s pig-eating-a-pig vignette saw a 2K zip as a backlight (with a 2K spacelight filling the first third of the world, and bleeding into his zone). Our clown’d Uncle Sam was dinged with a Source 4 as a key. Our bathing Amazon princess, Jen, shared the 2K zip with Avi, but got her own 300w special up and above. This had to be placed in such a way that I, as the operator, would not shadow her. The boxed mannequins received 300w specials as well, and the woman suspended by paracord inside the box also received a Source 4 topper. Two cross-key Source 4’s illuminated Meowtha on the lyra, which was suspended from the same beam. Meowtha is an incredible aerialist, but for safety’s sake (none of us trusted the beam), we had to limit what she did on the rig to something simple and safe. Finally, a rear 2K zip added a backlight for the dogs playing poker and betting the pig head.

My personal favorite moment of this scene is when we dim the entire world and throw a spotlight onto Pancho via a Source 4 focused adjacent the dog poker scene. When he sings, “I bet you think this song is about me…” and steps himself out of the spotlight, we knew we had some magic. It was so perfectly literal.

Moving into the banquet hall, we again employed 2K zips, this time to illuminate the St. Andrew’s cross BDSM scene in the background of the banquet table (¾-behind), and, similarly on the reverse side, the posing models. Chandeliers hung off on this side as well to give some extra flare. Two cross soft 2k zips above the banquet table were offset by the 4’ Kino select, rehung directly above the table on the day above the table to help facilitate the color change from gold to purple. Behind each fire spinner a 2k zip was panned on as a backlight, and behind Pancho a series of three Source 4 backlights was employed. A couple 300w accent lights illuminated things like the columns on either side of the stage. Finally, the last of our Source 4’s were employed for Pancho’s frontal illumination, and one was also mounted to give that beautiful shadow from the deer woman’s mask, painted with care onto the ground behind her for the final frame.

Our two FX lights came in very handy for this scene. The zips that were placed above each side of the table and angled across were faded down during the firing sequence, and only the 4’ Kino Select remained (because we were able to turn this red easily). Two red world workers, now liberated, stand tall after the firing, fists in the air. Did you catch them? And the SkyPanel was reposition behind and left of the stage’s 20×40’ black duvetyne for the moment when the gun fires. This had to be trigged manually, and my dear friend Colin Trenbeath was tasked with hanging out at the top of the 14-step during the shoot, ready to get it going at the right moment.

Since the shot was a continuous one-take, we had to do a handful of trickery behind the scenes. For example, as soon as we were done with the intro beat with Uncle Sam and the toy soldiers, he was cued to then run behind camera and make his way to have a seat at the final table. As Pancho jumps onto the stage, I actually had to jump up onto the banquet table myself so as to hide all of the characters that were about to be killed. Afterwards, I climb down from the table, and spin my way around to pay off the world (with now completely different lighting). All of the lighting cues were accomplished by the Boys setting up scenes in Luminar, and triggering them manually based on where I was with camera in the moment. Simultaneously, all of the characters had their own marks, directions, and actions to fulfill. We spent hours rehearsing this scene, like a stage-play, before we attempted to roll one on camera. We knew we had when the room erupted in applause, and the cooler full of beers was slid out to celebrate with. Truly magical.

THE WRAP PARTY

When we first started prepping for Strangetown there was always this notion that we would throw a big party as soon as wrapped our second and last day of shooting (which was thusly scheduled for a Saturday night). The idea was that it’d be a great way to instantly thank folks for their hard work with a few cases of beer and a DJ’d dance party, all right there on the set they’d spent so many hours on. So as soon as we wrapped we had to immediately wrap the set, make it safe, and transition all the lights to party mode. This turned out to be a bit of a mad fury (and in retrospect, we probably should have cleared the set first so we could make it safe), but in the end we laughed, we cried, we danced, and we stayed up til sunrise honoring the space that had been our home-away-from-home for the past several months.

STRIKE

One of my proudest moments of the whole shoot, from a lighting perspective at least, was during strike. We only had a day to wrap every light, cable, and piece of grip gear before we had to get it all back to DTC. We laid out every crate we had and as things came down from the rigging in the sky, they were organized into bins and counted against our list. When we returned to DTC, the only item that was missing from our original order was the bag for the 8×8’ gold lame that we hung above the Gold World. The team at the shop had probably been taking bets against how much stuff we’d have in Lost and Damaged (it was a truly massive order for a passion project), and to show up owing them an $8 bag (that was likely just thrown away by accident by a PA or something) left everyone at the shop thoroughly impressed. It was our small way of thanking them for their hard work in prepping all the gear for us.

LESSONS LEARNED

If we don’t learn something new on every shoot, we’re working hard enough. Strangetown was no exception. There were obvious things we would have liked to have had that weren’t possible: more time, more money, more crew. Specifically though, if we had more time, we could have arranged our days a bit better so the scissor lift wasn’t constantly having to work around the art department. This, as mentioned earlier, was a constant negotiation. The advantages of more money and more crew are obvious.

One specific “gotcha” I learned from The Boys regarding my favorite lighting unit, Source 4’s, was: always rent the widest lens. I had rented specific sized lenses in a handful of places based on photometric calculations I did via ETC’s web services. My thought was that being more specific would save time (and help ease the demand for lenses from DTC). In practicality, the amount of light that would have been lost by using a wider lens with an iris (another consideration) was negligible compared to the amount of time that ended up being lost sorting units and insuring the proper one was in the proper place. Had all the units just been 50-degree lenses with irises in each one, we would have had more immediate fine control with less time spent on the day. An important lesson.

Second “gotcha” is on the topic of safety. During our second day of shooting, we had dozens of people in an enclosed space and practical fire effects happening. Our 1st AD on the day, Eric Sheehan, bless his heart, kept us all aware of our exits and what an emergency protocol would look like. But it was Savage Paul who at one point asked if, in our fancy iPad app, we had a way to quickly set all of our lights to on at 100% brightness. Up until that moment, we had only programmed highly specific cues in each of Luminar’s “scenes.” Having a one-tap way to illuminate every light in the building to full brightness was a fantastic idea that we, fortunately, never needed to use. Will keep that one in the toolkit, for sure.

Finally, Eric Corriea (seen below rigging the Kino select) taught me a valuable and memorable lesson: “rig to wrap.” In a feeble attempt to help him and Zac get a little further ahead, I was working through the late hours one night running cable and decided to run one of the 100-amp bates cables for them in the sky. Trevor Banta jumped on board to help (he was basically functioning as a swiss-army-knife all week). He and I got to work getting the bates cable across the set by throwing it over each and every one of the steel support beams in the warehouse using a “fishing hook” device we constructed – a painstaking and time-consuming process. Doing it this way (with the cables hung above the cross beams) meant it would be just as much of a chore to take down as it was to put up, with the cable needing to be fed through each piece of the pseudo-grid. This was wrong. The proper way to do this, I learned, was to simply tie the cable to the grid with some sash cord, keeping the actual bates cable below the grid. When done this way, all you have to do to wrap the cable is rip out the knot and watch it fall to the ground. I will happily own that one, and will thus never forget it.

FINAL THANKS

I need to share a heavy dose of gratitude to DTC Grip & Electric in Oakland. Without Darcy’s unrelenting support, we would not have been able to produce something of this caliber. From the get-go she and the whole warehouse team were on our side. They helped us secure a massive package on a tiny budget, and make sure we had all the necessary safety equipment. It should be noted that after the shoot, DTC used the money we gave them and put it directly into throwing a party for their entire warehouse staff — a strong show of how they value their communities on both sides of the G&E order.

Next, the Boys. With minimal rotating support from a few hard-working extra hands (when we had them), Zac and Eric together wired, hung lit, and programmed each of the 7 environments essentially by themselves in two days. Our budget was tiny, and our crew was tiny, but nonetheless these two absolutely astonished everyone with their ability to light and control this set as a two-man team. I’ve known Zac and Eric for years, and this was certainly one of the most challenging (while hopefully also one of the most rewarding) projects I’ve ever asked them out on. They did a stellar job, the results are palpable, and I’ll be buying the first round for another few years. Tons of gratitude to these two.

Eddy at Event Magic was one more true hero of the project. Through the grapevine we heard he was looking to start clearing his inventory and Treigh, master production designer that she is, suggested we go take a look. We hunted through every square foot of his warehouse and tagged dozens of items for pickup with a rented box truck. Many of the large props you see from the film were modified, painted, or upcycled from Eddy’s gracious donations. The “haul” is showcased below.

I’ve gone in detail with a few of the folks that were essential specifically to the lighting of the set, but I also want to thank the camera crew who helped keep things moving throughout production. Rikuto, thank you for keeping us sharp. Jes, thank you for saving our ass with the Nucleus. Annie, thank you for keeping us organized. Ryan and Justin, thank you for your flexibility and swinging between duties. And Colin, thank you for keeping me sane.

Outside the world of camera and lighting — thank you to the entire cast and crew who made this thing a success. From the producing team who kept the train on the tracks, to the vignette leads and art department team who produced massive and beautiful art on a tiny budget, to the performers who rolled with the punches and the long hours to share their incredible gift, to our chefs who kept us fed, to the production team and PA nation that kept the set lubricated, all the way to our late night DJ’s that fueled our after party, and to everyone in between — thank you. They say it takes a village, I think it takes a tribe, and I’m proud to be part of ours.